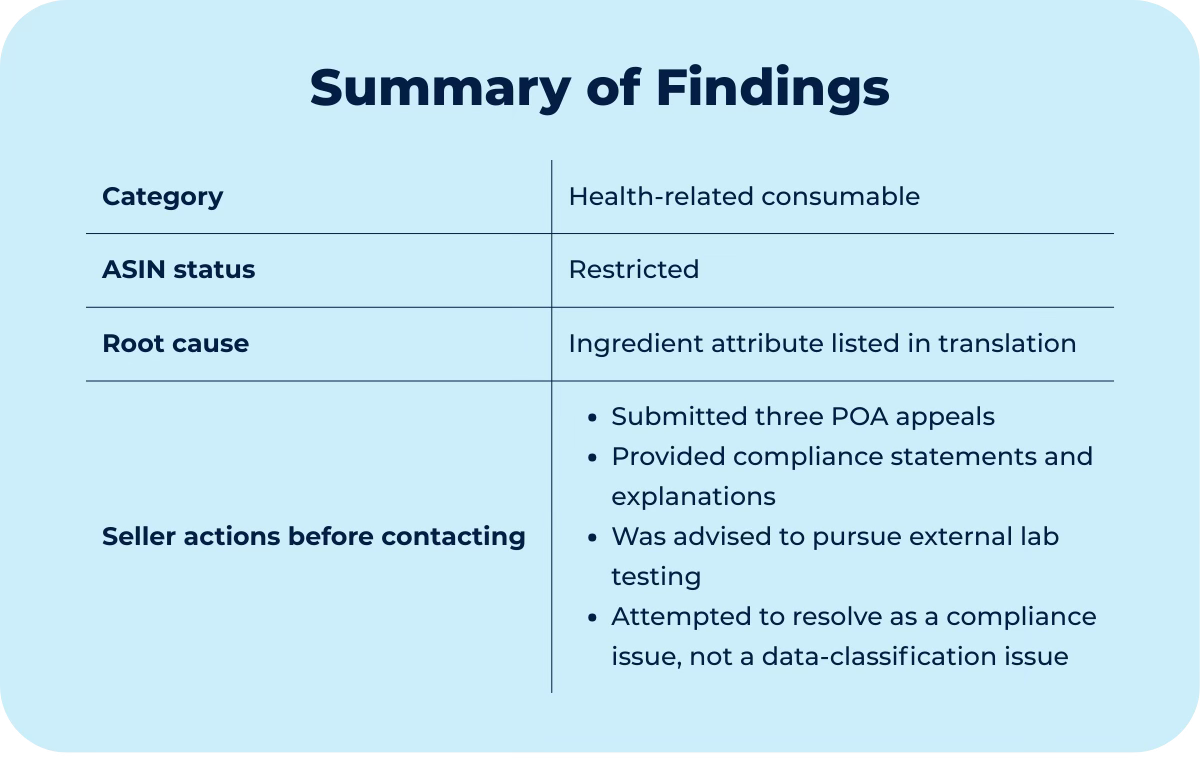

Case #003 – When Translation Triggers Become Compliance Violations

A compliant listing was restricted by translated backend attributes that the seller couldn’t understand or edit.

Context

When a listing is blocked by its own translation

This case began with one of the worst sentences a seller can read:

“Your product contains a restricted ingredient.”

A top-performing product and its bundles were suddenly restricted, sales stopped entirely, and the listing disappeared from search. Before coming to us, the seller had already hired a well-known Amazon consulting firm. Their approach was straightforward (and costly):

They confirmed Amazon had detected a prohibited ingredient in the product.

They did what felt “logical” and submitted appeals, stating that the product doesn’t contain the flagged ingredient. All three were denied.

Then they advised the seller to run lab tests to prove to Amazon that the ingredient wasn’t present.

That’s where the case went off track, because every action focused on disproving the restriction instead of identifying the trigger. The operating assumption was: “Amazon says there is a restricted ingredient, so the task is to prove it is not there.”

When the seller contacted us, we started by carefully reviewing the listing content (front and back). There was no mention of the ingredient, no indirect phrasing, and no formulation changes. Yet the restriction remained. That discrepancy became the key signal. The problem wasn’t the product. It wasn’t the label. It wasn’t even the US listing content.

The problem was the data describing the product inside Amazon’s catalog.

Diagnostic

Why Amazon flagged a product that never contained the ingredient

Amazon does not enforce ingredient compliance based only on what sellers can see or edit on the listing page. Detail page text, bullets, descriptions, and A+ content are just one layer. Enforcement is increasingly driven by catalog attributes, auto-generated translations, and data signals from other marketplaces and external platforms (such as Walmart, TikTokShop, or Shopify) that sellers often cannot directly view or control.

In this case, the ASIN was flagged for containing chlorhexidine, an ingredient Amazon treats as restricted and subject to FDA oversight. This restriction also made the catalog classify the product as a medical device. The key issue was that the trigger did not originate from the brand's listing content.

The root cause only became visible once the investigation expanded beyond the main and original Amazon marketplace (the US).

At an earlier point, the seller had enabled global selling as part of an expansion attempt. No inventory was sent and no sales occurred, but Amazon automatically created listings in those regions and populated them using its own translation systems.

Here is where the real root cause appeared:

The German marketplace listing contained the ingredient term

The term was introduced via Amazon’s auto-translation system

Amazon (not the seller) held contribution rights so that it couldn’t be edited

During the same investigation, we also found a health claim in the Spanish translation linked to the US catalog.

These fields were not “visible” on the live .com detail page, but they existed in backend catalog data. So even though the product never contained chlorhexidine and the original content never mentioned it, some attributes in the translated versions of the product did.

And if those attributes existed, they served as the authoritative signal for enforcement. Every appeal after that point was evaluated under the assumption that the ingredient was present, regardless of what appeared publicly.

The enforcement wasn’t reacting to the physical product or the original content on the listing. It was reacting to Amazon’s own translated and enriched catalog data.

Thought Process

The question that changed the case

Once we understood that the root cause wasn’t originating from the US listing, the question stopped being what is wrong with this product and became how did this data get into the catalog in the first place.

When sellers enable global selling, Amazon doesn’t wait for them to manually build every listing in every country. To accelerate global expansion, Amazon automatically generates international versions using AI translation and catalog enrichment systems. Those systems reuse existing data from the primary Amazon marketplace, infer missing attributes, and populate fields across languages and regions.

That speed comes with a tradeoff: accuracy.

Auto-generated attributes are not validated against product formulas or regulatory constraints. They are built using pattern recognition, similar ASINs, and historical catalog data. Once those attributes are created, they no longer behave like editable listing text, they become structured catalog data.

This is where data augmenters come in. These are internal Amazon contributors and automated processes that add, translate, and “improve” catalog attributes. When they populate a field, Amazon treats that contribution as authoritative. Sellers usually cannot overwrite it through Seller Central or flat files, even when it is incorrect or triggers enforcement.

That is why the restriction persisted.

Appeals were not being evaluated against the US content. They were assessed against the translated ingredient attributes generated by Amazon’s systems. As long as those structured attributes existed, enforcement logic had no reason to change, regardless of the product’s real formulation or how many explanations were submitted.

Recognizing that flow reshaped the strategy entirely. The issue was not about proving compliance. It was about correcting the upstream data source that the enforcement system trusted. Once we shifted focus from arguing the case to changing the catalog attributes themselves, the path forward became clear, and the restriction was lifted.