Case #002 - When Amazon’s Policy Outruns Its Process

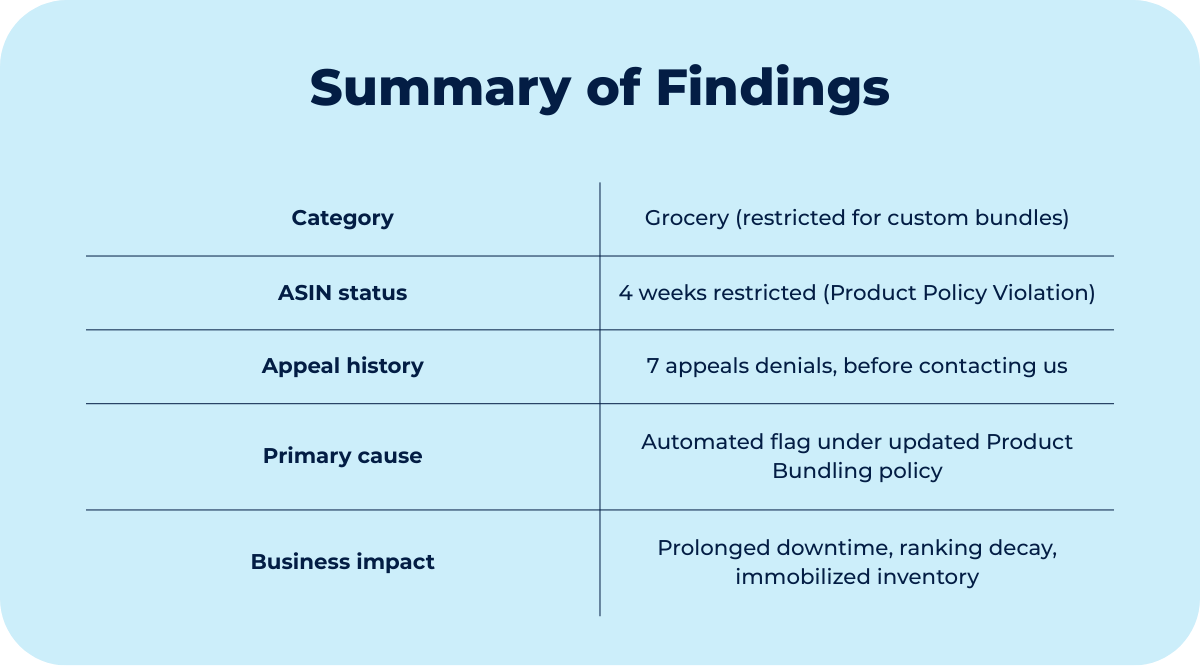

A compliant bundle lost 30 days of sales because Amazon updated a policy without actualizing their internal processes.

Context

A month of silence: when compliance hits the wall

This case began the way many of the most frustrating Amazon issues do: with silence.

A high-performing grocery bundle had been down for over a month, costing the seller more than $30,000 in revenue.

The seller had done everything by the book: calls, chats, escalation forms, and even Account Health follow-ups. Every reply came back identical: “This product violates Amazon’s Product Bundling policy.”

No context. No instruction. No path forward.

What made the situation especially difficult was that nothing obvious appeared to be missing. The bundle had proper packaging, clear external labeling, and valid letters of authorization (LOAs) from every brand included. On paper, the listing looked exactly the way Amazon expects compliant bundles to look.

At first glance, the explanation seemed straightforward. Amazon had recently rewritten its Product Bundling policy across several sensitive categories, including Grocery & Gourmet, so the natural assumption was that something was missing.

But that wasn’t the case. The bundle had already been aligned with the updated policy, too.

So why did Seller Support keep insisting the listing was non-compliant?

That question marked the turning point of the case, shifting the focus away from the listing itself and toward something deeper in Amazon’s enforcement process.

Diagnostic

Why this policy changed and why the system broke

To understand this case, we need to step back from the individual listing and examine why Amazon rewrote its Product Bundling policy in the first place.

Historically, bundles were one of the most flexible listing formats in the catalog. Sellers could combine complementary products, such as coffee and filters or shampoo and conditioner, often under their own brand or even as “Generic.” Amazon tolerated this for years because it increased convenience and incremental sales.

As the marketplace scaled, that flexibility became a liability. Counterfeit products, safety concerns, and expired or repackaged items became more common, particularly in high-trust categories like Grocery and Beauty. At the same time, multi-brand bundles began to dilute brand consistency across the catalog.

Large national brands, many with direct supplier relationships with Amazon, had little control over how their products were presented in third-party bundles they didn’t authorize, approve, or manage. From Amazon’s perspective, this created both a brand trust issue and a partner relationship issue.

The response was a fundamental policy reset.

Under the rewritten Product Bundling policy:

Only manufacturer-created bundles are allowed.

Mixing different brands under a single ASIN is prohibited.

Private-label or “Generic” brand names cannot host multi-brand bundles.

The sole exception is gift baskets, which require valid letters of authorization (LOAs) from each brand included.

Against that backdrop, the listing itself wasn’t the failure point. The breakdown occurred at the enforcement layer.

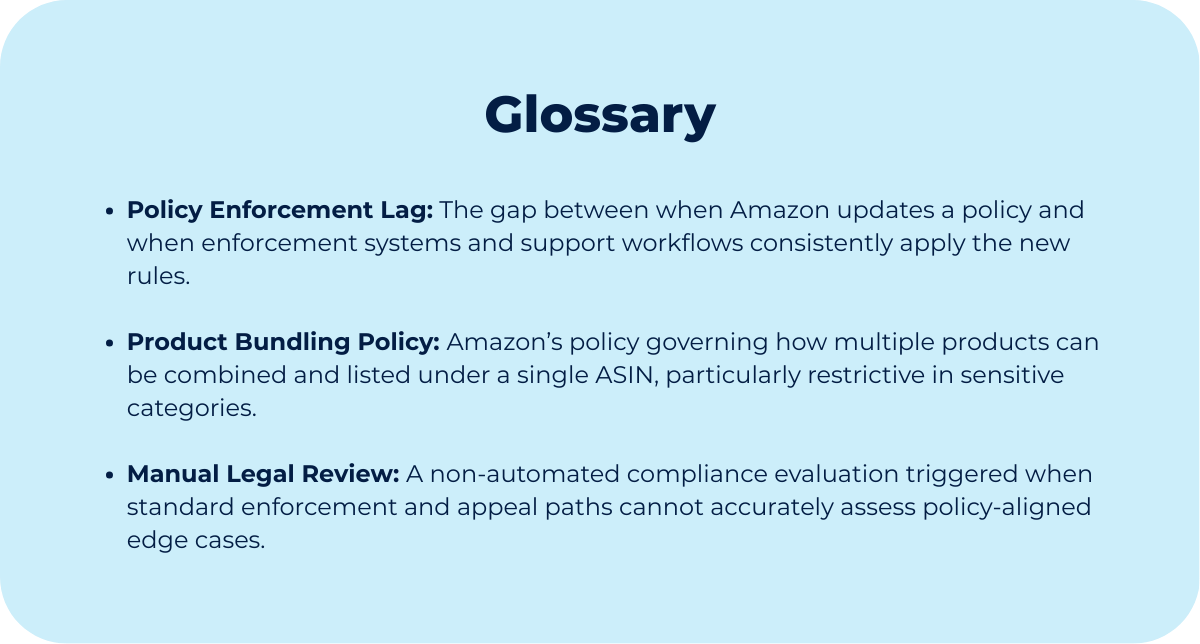

Amazon’s automated validation systems and support workflows had not yet fully synchronized with the updated rules. Enforcement moved immediately, but the mechanisms responsible for interpreting edge cases were still operating on legacy documentation and outdated decision logic.

As a result, reinstatement requests were routed through support paths that lacked both the context and the authority to recognize compliance under the new framework. Cases circulated between teams applying inconsistent and obsolete criteria.

Once this pattern became clear, the issue stopped being about the rejection and began to look more like a process gap.

When policy moves faster than enforcement, compliant listings don’t fail because they’re wrong, they fail because the system evaluating them hasn’t caught up.

Thought Process

How we think about Amazon policy changes

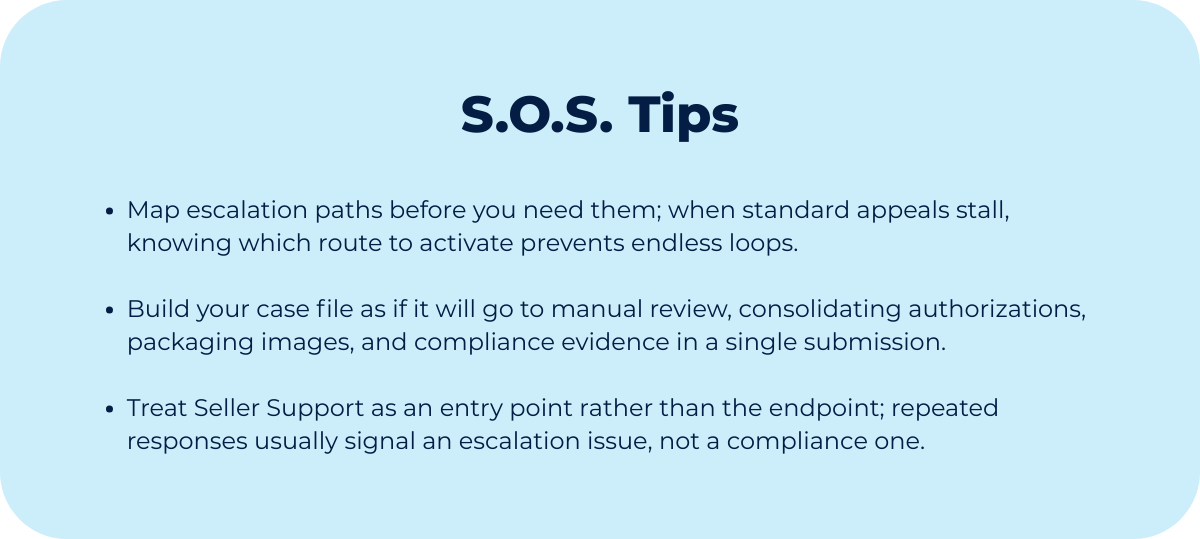

Once it was clear that the issue wasn’t the listing or the policy itself, the focus shifted from what went wrong to how to move forward within a misaligned system.

When Amazon rolls out policy changes, different parts of the organization absorb updates at different speeds. This creates temporary gaps where compliance exists, but recognition does not.

To operate inside those gaps, we rely on a simple alignment model. For enforcement to resolve cleanly, three layers must converge:

Policy intent: what Amazon has formally decided should be allowed.

System behavior: what automated tools are currently flagging or blocking.

Decision authority: which internal teams are actually empowered to interpret and override enforcement in sensitive cases.

At this point, re-proving compliance was no longer the goal. That had already been established. The objective was to identify where alignment had broken and which layer could realistically be influenced.

Standard appeal paths were no longer effective. Those workflows are designed for clear violations, not for edge cases created during early policy rollouts, and re-entering them simply recycled the listing through the same decision loops.

If the blockage originated in automated enforcement but required human interpretation to resolve, then progress depended on reaching a team with both current policy context and the authority to make a binding decision.

That led us to the only question that mattered: Which internal team was actually equipped to evaluate this case under the updated policy, in real time?